November 2021

By Brendan Lee, Assistant Principal, Blaxland East PS

Have you ever wondered why kids are able to sit in the one spot and spend hours-on-end playing video games?

Yet, these same children can’t sit still in the classroom or give up at the drop of a hat if they are struggling with a task?

Gamification is about applying game mechanics in a non-recreational environment. In other words, using game aspects like progression, points, choice, rules, achievements, avatars, feedback, cooperation and bonuses to increase motivation, focus and so that the learner experiences the ‘desirable difficulties’ in the environment they are learning through.

“The research tells us that PE needs to be done differently, and this is an example of PE being done differently,”

Shane Pill Associate Professor, from the Flinders Sport, Health, Activity, Performance and Exercise (SHAPE) Research Centre.

Think about how video games are developed. They have different difficulty levels (easy, medium, hard) and set it up so that the player progresses through the game with each stage gradually getting harder. Gamers get ‘hooked’ from the start because they know what the goal is, they experience success and ‘desirable difficulties’.

ImSporticus wrote in his blog drowningintheshallow:

Elements used to ‘gamify’ educational contexts are grouped in three categories:

- Dynamics: this is the highest conceptual level and it includes narrative, progression, emotions, constraints, relationships.

- Mechanics: this is the second level and it includes the elements that makes the action progress: rules, challenges, chance, competition, cooperation, feedback.

- Components: this is the basic level and it represents tangible elements: avatars, achievements, trophies, badges, points, leaderboards, levels

The theory behind gamification

Gamification as a pedagogical approach can also follow these theories to support its practical implementation.

Achievement Goal Theory says that mastery goals put the “focus on learning and mastery of the content or task (Kirschner and Hendrick, 2020).” It takes the focus off comparing their performance to others and avoids looking at how they have been judged. Getting better is continuous while being the best has an end point.

Desirable difficulties: Bjork & Bjork, 2011 came up with the term ‘desirable difficulties’, which can be described as pitching the task at the precise point, not too easy and not too hard. It can be enhanced by using things such as spacing, interleaving and elaboration.

Self-Determination Theory: The theory is particularly concerned with how social- contextual factors support or thwart people’s thriving through the satisfaction of their basic psychological needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy (Ryan and Deci 2017)

- autonomy: a sense of initiative and ownership in one’s actions

- competency: the feeling of mastery

- relatedness: sense of belonging and connection.

Intrinsic motivation (when participating in activities because they enjoy it) has many benefits within an educational setting with studies showing improvements in both school achievement and performance and self-esteem (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Extrinsic motivation, from a self-determination theory perspective has four major subtypes:

- External regulation: praise, rewards or punishment avoidance

- Introjected regulation: seeking approval, avoid demonstration of failure

- Identified regulation: self-identified goals

- Integrated regulation: where the behaviour is completely linked to personal values and interests.

Identified and integrated regulation are still extrinsic because they do these activities not because they enjoy them, but because they link to their goals, values and interests. It might be something like deliberate practice.

What can educators do to move towards autonomous motivation?

- Offer meaningful choice: leads to increase in ownership

- Take student interest into account when designing lessons/tasks

- Give students opportunities to speak and listen to them

- Acknowledge improvement and mastery

- Make time for independent work

- Offer structure with clear goals, expectations and rules

- Appropriate level of scaffolding

Planning a lesson using gamification

- Work out what your base learning intentions and success criteria are. What do you want everyone to know/be able to do by the end of the learning sequence?

- What are the possible ways that they could show they know/can do that? This is where you start to come up with ways to give choice e.g. they can choose the equipment they use, how it is presented,

- How will you get them curious? Think about their interests, ‘hot topics’ or exciting themes. What sort of storyline can you put together? Shimamura, 2018 and Willingham, 2021, talk about the importance of creating curiosity through asking interesting questions, exploring new environments, asking “aesthetics” questions (How they feel about things) and through storytelling.

- Where will they start and how do they progress? Look at the general ability levels of the group you are planning for. What will be a good starting point so that everyone can experience success? Shimamura, tells us that pleasurable experiences stimulate the release of dopamine. The same neurochemical that is activated by cocaine, nicotine, eating chocolate, looking at attractive faces and listening to music. When we think about past experiences, we want to think about good ones, this will increase the motivation of our students to get that dopamine hit again.

- What are the mechanics of the lesson that you need to vary to support students to increase their understanding of your learning intentions? For example, if you’re designing a game around kicking, you might give bonus points to students who show exemplary technique.

- What modifications can be made? To ensure it is accessible for all, what areas can be adapted? Can some students use bigger balls or targets?

Examples of gamification

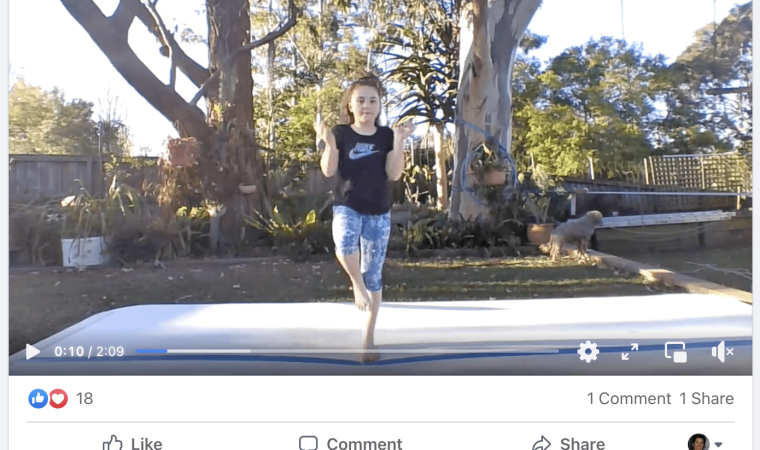

Cross the River Scenario

You have gone for a bush walk in Katoomba with some friends. A huge storm comes and a large tree falls down and blocks your path back to the carpark. Your only way back to safety is to cross the river!

https://twitter.com/learnwithmrlee/status/1448481539877060615

The students have a set number of items to use to get their whole team to the other side. The focus was on learning how to encourage others and build a sense of belonging.

- Level 1:Get to the “Island”: Achievable for everyone

- Level 2: Cross the River: Have to travel further

- Level 3: You Lost a Rock – lose an item

- Level 4: Cross the River – Visual impairment

- Level 5: Cross the river – Broken leg

- Level 6: Double Up: Work with another team

I also gave students the option of using lives, where they had a chance if a body part touched the ground. Another variation was to give some groups harder objects to balance on.

Need more support in creating engaging PE Lessons?

Reimagining Physical Education is a new thought-leading workshop series from ACHPER NSW. Designed to support teachers and faculties to review current practices, reinvigorate programs and increase engagement for all students, the workshops are being held at locations across NSW during 2021 and 2022. View the calendar>

More information on Gamification

- Andy Hair wrote an article, Gamification changing engagement

- Michael Ginicola has a stack of Gamification resources on his website

- Nathan Horne interviews Carl Condliffe in his PhysEdcast

- A blog post from The PE Specialist on Gamified PE

- Martin Langston recently wrote a great blog post about Gamifying PE Lessons – application to a Badminton lesson.

- An article from Flinders University on Putting gaming in the PE mix. It looks at the intersection between PE and video games.

The Gamification of Everything – Including Phys Ed a blog article form Mr Robbo

References

Bjork, E. L., & Bjork, R. A. (2011). Making things hard on yourself, but in a good way: Creating desirable difficulties to enhance learning. In M. A. Gernsbacher, R. W. Pew, L. M. Hough, J. R. Pomerantz (Eds.) & FABBS Foundation, Psychology and the real world: Essays illustrating fundamental contributions to society (pp. 56–64). Worth Publishers.

Corepal R, Best P, O’Neill R, et alExploring the use of a gamified intervention for encouraging physical activity in adolescents: a qualitative longitudinal study in Northern IrelandBMJ Open 2018;8:e019663. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019663

Javier Fernandez-Rio, Esteban de las Heras, Tristan González, Vanessa Trillo & Jorge Palomares (2020) Gamification and physical education. Viability and preliminary views from students and teachers, Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 25:5, 509-524, DOI: 10.1080/17408989.2020.1743253

Kirschner, P.A., & Hendrick, C. 2020, ‘How Learning Happens: Seminal Works in Educational Psychology and What They Mean in Practice.’ David Fulton Inc

Price, Amy, Collins, Dave, Stoszkowski, John and Pill, Shane (2017) Learning to Play Soccer: Lessons on Meta-cognition from Video Game Design. Quest. pp. 1-13. ISSN 0033-6297 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2017.1386574

Shimamura, A. 2018, “A Whole-Brain Learning Approach for Students and Teachers.”

Willingham, D.T. 2021. “Why Don’t Students Like School? A Cognitive Scientist Answers Questions About How the Mind Works and What It Means for the Classroom. Second Edition.” John Wiley & Sons Inc