Dr Lynn Sheridan University of Wollongong, School of Education

lynns@uow.edu.au

Dr Dennis Alonzo

University of New South Wales, School of Education

d.alongzo@unsw.edu.au

Disruptions to teaching whether it is the everyday challenges or the crisis situations such as COVID-19 continue to contribute to the ‘job stressors’ that teachers experience when meeting the demands of the job. This is especially the case if teachers are required to engage in higher-than-normal efforts from which the individual does not adequately or easily recover (Meijman & Mulder, 1998).

We know that contextual and personal factors play an important role in determining work-related outcomes. Employees’ work-related outcomes are linked to job resources and demands. They can be physical, social, psychological, and organisational in nature. Whereas job resources are associated with positive outcomes, job demands are associated to high work pressure, emotionally demanding interactions, and less positive experiences (Bakker& Demerouti, 2017). Teachers who possess high job resources with social support and feedback, are more likely to be able to adapt and cope with the demands and will experience reduced stress from the job. The job demands of teachers – the everyday and particularly the demands that disruptions such as COVID-19 have impacted teachers’ overall job engagement.

As teachers, schools, principal and systems look for what can be done to keep teachers engaged with teaching (see Zamarro et al., 2021 -Brown Centre Chalkboard) it is important to consider what resources the job offers individual teachers (i.e., physical, psychological, social, or organisational aspects) that can help to reduce job demands and the associated costs.

What factors support resilience, and can enhance a teacher’s capacity to adapt to change?

What are the resources that individual teachers possess that can help them to navigate the everyday vicissitudes and the organisational stresses?

These questions are becoming increasingly important in the COVID-19 era, especially if we are to retain teachers and prevent further teacher burnout (Teacher: Educator Wellbeing). School leaders need to consider implementing a leadership approach that can enhance teachers’ adaptability and resilience.

Schools and leaders have a responsibility

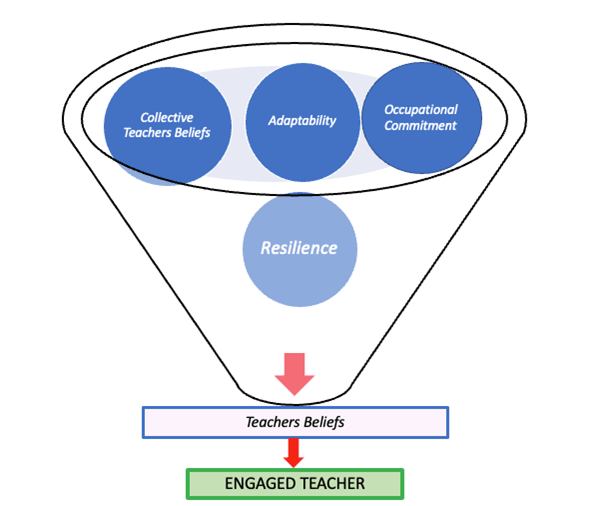

We know from a recent survey of 239 Australian teachers that those teachers who had increased sense of self efficacy were more engaged with the teaching job. In practical terms this mean that schools and leaders have a responsibility to invest in increasing teachers’ beliefs (e.g., induction, training, social support, mentoring, coaching) which can enhance teachers’ capabilities. It was also found that those teachers who were adaptive to challenges – the everyday and the crisis – where more likely to be resilient. It was found in this recent study that teachers’ adaptability and resilience were positively associated with their sense of confidence in the teaching role. Previous research has suggested that the ability to adapt is a protective factor against everyday stresses (Collie et al., 2020).

Supportive colleagues

Interestingly, being able to adapt, being resilient, is dependent on the context. The recent study found that having supportive colleagues was important job resource. It was associated with individual teachers’ sense of efficacy beliefs, with collective teachers’ beliefs seen to support the individual’s sense of efficacy beliefs. Having positive school culture where colleagues feel empowered and supported and are prepared to support others, is known to be an important job resource that can help to nurture job commitment. Principals and system leaders can capitalise on this human resource.

It may also be time to consider the importance of ‘collective’ support and belief. With ongoing school closures and increased isolation there is a need for informal and formal networks of support for teachers. This collective social bonding helps individual teachers to manage the stresses of the teaching role. School leaders can encourage and actively develop a culture of collective efficacy – ‘together we feel confident and capable to manage the change/challenges.’ This can benefit individual teachers as a part of the collective teaching team, which in turn, supports students to learn more effectively in a disrupted context.

Figure 1. Job resources for engaged teachers

What can teachers do?

- Mentor a more junior colleague or team teach with a less experienced colleague or one who might be struggling with a complex class – to better manage difficult emotional responses

- Engage in opportunities for social as well professional dialogue

- Shared learning experiences and stories – things that work to reduce feeling of isolation and promote teacher resilience

- Engage in help seeking strategies – emotion-focused and direct-action coping strategies

- Help others to depersonalize stressful events and focus on the positives of the job

- Establish realistic professional goal expectations

- Engage in the opportunities for relationship building and reflection within the busyness of the school week

- School culture – encourage effective praise among colleagues

What can principals do?

- Provide informal and formal social support, professional networks, and career development advice

- Provide authentic induction and training for new staff/junior staff

- Examine and readjust the workloads of individuals who are under emotional strain

- See performance as an opportunity for growth not necessarily accountability

- Trust that teachers can perform the role, allow them some autonomy with teaching decision-making

- Identify the process of positive adaption that occurred between teachers and their school culture

- Facilitate reflective training to promote adaptative strategies and resilience to attend to their own needs that arise from pastoral role with students

- Support teachers to develop good relationships with their pupils and colleagues

- Promote positive mentally healthy teaching and learning environments

- Provide opportunities for teachers to engage in help seeking strategies

- Pay attention to issues that create and add to the pressure on teachers, such as workloads, class allocation, behaviour management and peer relationships

- Develop a robust system that support teachers to feel welcomed and valued, whereby performance evaluation is a form of support.

- Remove the notion of ‘sink or swim’ from the teaching lexicon and the concept that feeling ‘battered’ is normal in school workplaces

- Ensure all teachers are well supported and that they have developed realistic expectations for themselves and their students.

A final thought

Disruptions to teaching is part of the job demand that teacher face. However, having teachers who are engaged in teaching is critical to quality teaching. Through the above suggestions, teachers and principals can provide the resources needed to sustaining teachers’ commitment – and better supporting those who are struggling.

References

Collie, R., Guay, F., Martin, A. J., Caldecott-Davis, K., & Granziera, H. (2020). Examining the unique roles of adaptability and buoyancy in teachers’ work-related outcomes. Teachers and Teaching, 26(3-4), 350-364.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/https://dx. doi.10.1037/ocp0000056

Meijman, T. F., & Mulder, G. (2013). Psychological aspects of workload. In A handbook of work and organizational psychology (pp. 15-44). Psychology Press.

Further resources

Granziera, G., & Collie, R.(2018). Being able to adapt in the classroom improves teachers’ well-being. The conversation Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/being-able-to-adapt-in-the-classroom-improves-teachers-well-being-95788

Kaskamanidis, Z., & Manuell, R. (2022). Researching education: Five further readings on educator wellbeing. Teacher: Evidence, Insights and Actions. Retrieved from https://www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/articles/researching-education-five-further-readings-on-educator-wellbeing.

Zamanarro, G., Camp, D., Fuchsman, D., & McGee, J.B. (2021). How the pandemic has changed teacher’ commitment to remining in the classroom, Brown Centre Chalkboard. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2021/09/08/how-the-pandemic-has-changed-teachers-commitment-to-remaining-in-the-classroom/